The Village Sun

In 1961, Jane Jacobs, author of “The Death and Life of Great American

Cities,” called city planning “a pseudo-science” that had “arisen on a

foundation of nonsense.”

Jacobs argued for an end to gigantic plans that relied on

“catastrophic money” and “centralized processes” and “standardized

solutions.” All that, she argued, just created “dead places” — like

today’s Hudson Yards.

More recently, Sam Stein, in his book “Capital City: Gentrification

and the Real Estate State,” chastised planners for serving the interest

of Big Real Estate rather than the public good.

It is true that for all their talk of serving the public good,

planners do appear to dislike citizens. For one, they are trained to

think of citizens as generic NIMBYs standing in the way of their ideas.

Moreover, as a profession, they tend to overly admire Robert Moses, the

man who imposed his will on New York City in a way that was top-down,

cruel and racist — not to mention plain destructive.

Moses’ defenders always respond, “At least he got something done,”

and argue for more central planning power, skirting the issue of whether

better plans might have been made in another way.

These issues have returned anew with the announcement of a proposed

planning law that City Council Speaker Corey Johnson is promoting. The

law is a very bad one. Citizens should definitely object to it, and stop

this law before the city puts a new Robert Moses into power.

The purpose of the law is, to quote from it: “to prioritize

population growth, where applicable, in areas that have high access to

opportunity and low risk for displacement.”

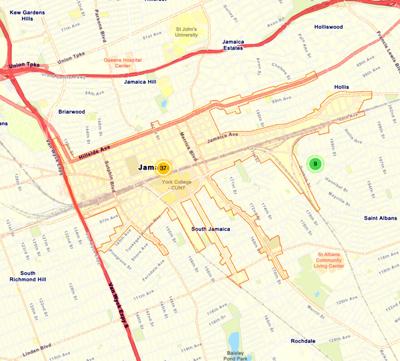

“High opportunity,” “amenity rich” and “well-resourced” are code

words among planners for overdeveloped neighborhoods in the historic

core of the city — Manhattan south of 125th St., Downtown Brooklyn,

Brownstone Brooklyn around Prospect Park and the East River. (See Vicki Been’s report “Where We Live.”)

These are high-density, overdeveloped, often historic places with

lots of subways, good schools, good parks, good grocery stores and short

commutes to Midtown and the Financial District.

Oddly, these areas are also places where Big Real Estate profits are

highest and where most of the new development since 2010 has already

been built. Why then is the planning law so laser-focussed on driving

growth to the already denser parts of the city, before the planning is

even conducted? Why does a new all-powerful Director get to assign

housing targets based on this high-opportunity theory? The law has

planning exactly backwards.

We are supposed to use planning to figure out and debate where to put

people (a.k.a. “density”) and infrastructure, not to do end runs around

communities and drive new density to predetermined areas of the city!

Here are nine things wrong with the proposed “comprehensive planning” law:

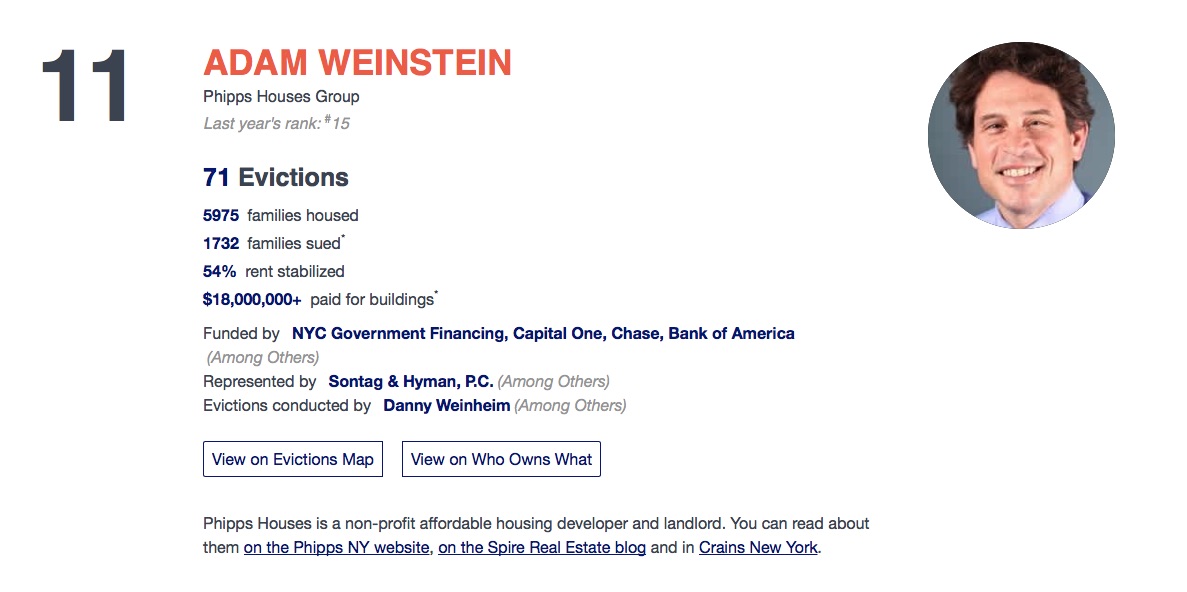

1.) It fails to address the elephant in the room: the revolving door

between Big Real Estate and government, thus undermining the legitimacy

of the process. Big Real Estate has already captured many of the

land-use regulatory agencies of the city; it thus imposes its vision

upon us through its people who run the Department of City Planning, the

Economic Development Corporation and the Board of Standards and Appeals.

See, for example, my op-ed “Fox Guarding the Henhouse at City Planning.”

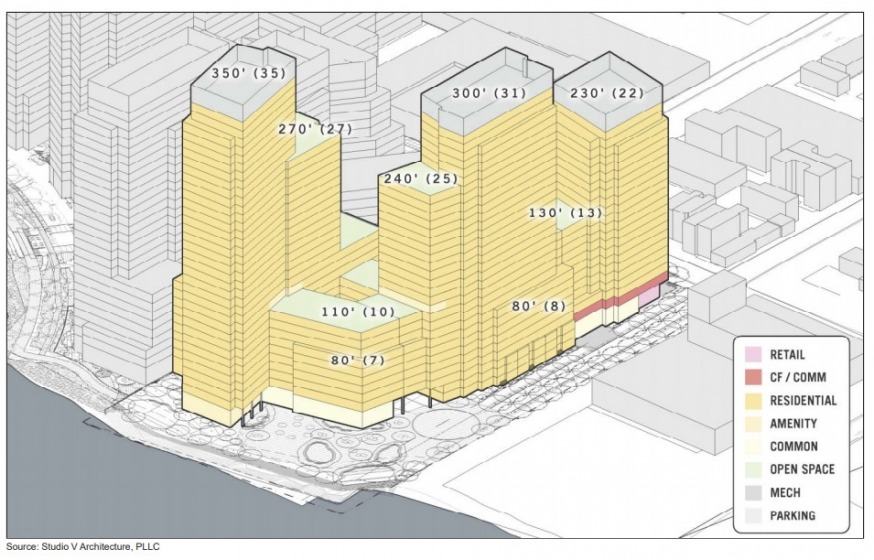

2.) The proposed law presupposes that the only way to deal with high

housing prices is to obsessively build hyper-dense (and tall) near

transit, which is what we have already been doing, based on a

discredited trickle-down housing-supply theory. It’s a planning approach

arising from a bad theory.

3.) It presupposes that the only way to deal with displacement risk

is to build like crazy when, in fact, displacement risk needs to be

managed in the first instance through legislation. Universal

rent stabilization and the Good Cause Eviction Act would largely solve

most of the displacement problem. Incremental building of more

public-social housing units at the low end of the market would deal with

the rest.

4.) It imposes Soviet-style housing targets on “low risk for

displacement” neighborhoods, without having had binding public policy

discussion about the upper limits or lower bounds of density. What kind

of city do we want and how should we spread the benefits and burdens of

density? The law presupposes that density can be infinite.

5.) The legislation presumes the scientific legitimacy of a dubious

“index of displacement risk” that gets coded into law. This is just not

credible. Such indices are built on a host of assumptions and not valid.

Displacement risk is a political phenomenon as much as a market one.

6.) Also, the planning law ignores key questions for public debate.

For example, when are we too dense to have a livable city? When are we

not dense enough? How should density be distributed? Should it be

distributed more evenly, like peanut butter on a slice of bread, or all

piled up in the historic core? And who should decide these questions,

the Director or the citizens of the city? All this is simply ignored,

even though these questions are the very heart of planning!

7.) At no point can neighborhoods, residents, taxpayers and citizens

vote on any plans at any time. There is no voting, no referenda, no

democracy. In other words, the proposed law is profoundly

anti-democratic.

8.) Under the proposed law, the housing targets for each neighborhood

rely on a bad theory that Big Real Estate loves: New population growth

should be targeted to existing “high-opportunity” areas. That’s an

invitation for selective overdevelopment, leaving the historic parts of

our city vulnerable to more demolition while ignoring the investment

needs of currently “low opportunity” neighborhoods.

There is also this troubling fact: Residents of low-amenity

neighborhoods have clearly said they don’t want to move. (See the city

report “Where We Live.”)

They want their existing neighborhoods to have amenities every bit as

good as the neighborhoods in the core. They just don’t want to be

gentrified out — or, rather, displaced.

9.) The law strengthens an already king-like mayor and recreates a

too-powerful Robert Moses figure in the form of “The Director.” Citizens

would not be able to reject this person.

Procedurally, here’s how the planning system would work: The mayor

would appoint a Robert Moses-like figure called “The Director.” The

Director would produce research reports on a lot of topics, all required

by the new law — which is O.K. Trouble arises when the Director is told

by law to create housing targets (Soviet-style) for how much new

housing each neighborhood (in high-opportunity/low-displacement areas)

must produce.

Procedurally, here’s how the planning system would work: The mayor

would appoint a Robert Moses-like figure called “The Director.” The

Director would produce research reports on a lot of topics, all required

by the new law — which is O.K. Trouble arises when the Director is told

by law to create housing targets (Soviet-style) for how much new

housing each neighborhood (in high-opportunity/low-displacement areas)

must produce.

The Director would create three scenarios for each neighborhood to

accommodate their assigned housing targets. The City Council would pick

one of the scenarios. If they said, “None of the above,” the Director

would then pick a scenario for them. The scenarios would get bundled

into a “comprehensive” 10-year plan for the entire city, approved by the

City Council to become law.

Developers would have to convince the Director that a new development

was consistent with the plan. If it was, they could avoid public

review, citizen outcry or deference to the local councilmember for the

particular project. A few public hearings are built into the process,

but they are just advisory white noise, like they are today. Citizens

and taxpayers never get to vote on the plan.

While this procedure sounds plausible for things like roads, schools,

transit, parks, trash disposal, libraries, sewage treatment and

tunnels, this plan is not really about those things. It’s really about

requiring each neighborhood to fill those assigned housing targets.

The law creates new committees to work with the Director, with

trivial, advisory roles. For example, the mayor, borough presidents and

the City Council would appoint a 13-member “long-term planning steering

committee” made up of demographically diverse “experts.” Their role

would be to give advice to the Director — who could ignore it. The

steering committee would also appoint five borough committees, which

would provide borough-specific feedback at various points in the

planning process. Their advice would also just be white noise. Community

boards would do nothing different than what they do now.

You can sign up to testify in person or submit written testimony here.

:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22706736/070721_parade_brad_lander.jpg)